外国人の方々、死んだ後のお墓は大丈夫ですか?…宗教や国籍等が異なる外国人のお墓の問題(上)

(Translated version follows this article.)

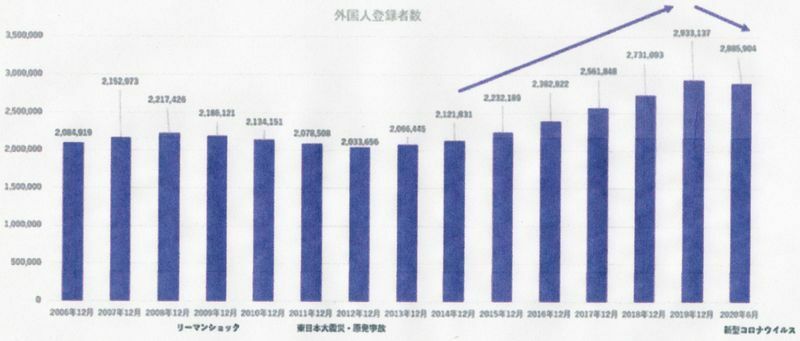

日本の在留外国人数は、2020年6月末で288万5,904人(出入国在留管理庁)となりました。外国人登録者数は、2013年以降年々増加し、毎年過去最高値を記録していましたが、2020年2月頃から急激に拡大したコロナ禍の影響で減少に転じています。しかしながら、2019年4月の改正入管法施行に象徴される、日本社会の少子高齢化による労働力不足が深刻化しており、コロナ禍も次のステージに移行しつつあり、コロナ禍が明ければ、外国人材の再増加は確実に起きると考えられています。

また日本の総人口は、2020年(令和2年)3月1日時点で、1億2,595万人(概算値)ですので、日本の人口における外国人材の比率は約2%となります。

出典:「日本に住む外国人の数は?日本で働く外国人の数は?日本に住む外国人まるごと解説~【2020年6月末/10月末 】在留外国人統計より~」 グローバルパワーユニバーシティ 2021年1月8日

このような現実は、読者の皆さんも、最近は実感として感じることも多いのではないかと思います。たとえば、近くのコンビニ、飲食店、建築現場などで、多くの外国人の方々が働いているのをみかけますよね。このように都市部だけではなく、地方でも国際化が進んできていて、外国人の労働者の方々がいないと、今の日本の経済はどうにも成り立たなくなってきていて、欠かせない存在となってきているのです。

このようにして外国人の方々が、日本社会の日常の中に根付き、普通に生活し、家族と暮らしを営むようになってきているのです。外国人の方々が、日本社会の普通の日常に入り込めば入り込むほど、どうしても避けられないいくつかの問題があります。その中でも、特に重要な問題の一つに外国人の方々のお墓事情があります。より具体的にいえば、国籍や埋葬方法の違いなどの理由から、日本国内のお墓にお骨やご遺体が納められない場合があるという現実です。

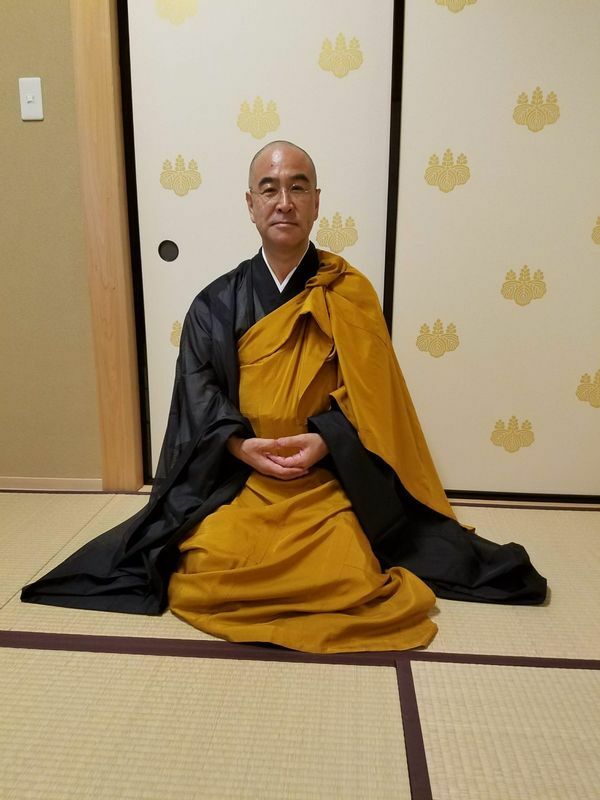

そこで、本記事では、その問題の解決に奔走されている石川県の徳雲寺住職の石毛泰道さんをインタビューするという形で、この問題について、2回に分けて考えていきたいと思います。

鈴木(以下、S):石毛泰道さん、本日は、よろしくお願いします。日本でも、多くの外国人の方々が普通に生活し、残念なことに、日本で亡くなる方もいて、その方々の埋葬やお墓の問題等が起きてきていますね。日本の現状および今後を考えると、今後ますますその問題が重要にならざるをえないと思います。その問題のこれまでと現状をお教えください。メディアなどでも、特にイスラム教徒の方の埋葬などが問題として取り上げられてきていましたね。

イスラム教徒の土葬問題から考える埋葬について

石毛泰道さん(以下、石毛さん):本日はよろしくお願いします。

たとえば日本で暮らすイスラム教徒は今や20万人近いという調査があります。今後も少子高齢社会における労働力の担い手としてイスラム圏である東南アジアなどからの外国人の流入が見込まれています、2050年には30万人を超えると言われています。

イスラム教の教義は、肉体を故意に失う行為は禁忌とされているために生きていた時と同じ状態で埋葬する、つまり土葬でなければならないのです。

他方で、日本社会における規制などで(注)、土葬埋葬できる墓地が限られているために、日本に居住しているイスラム教徒が亡くなっても、ご遺体を火葬せず埋葬できるイスラム専用の墓地が絶対的に不足しているために土葬が出来ない現実があるのです。そのために、彼らにとって、その墓地不足は大変な大きな問題なのです。

日本全国でもイスラム教徒の土葬が可能な墓地は数カ所しかありません、九州においてはこうした墓地が全く有りません。

S:そうなんですね。日本で、土葬埋葬できる墓地の実例をお教えいただけませんか。

石毛さん:たとえば、府中市にある都立多摩霊園があります。その広さは128ヘクタール(東京ドーム27個分)で42万6786人(2021年4月1日)が眠っています。この墓地は来年には開園100年(1923年)を迎えます。ここも、最近の傾向は墓の世話する親族が継承しない事や、次の世代に負担を避けるために自分達の墓を墓じまいして「合葬墓地」や「樹林墓地」に移すケースが多くなってきているようです。

この墓地の一角には、「外国人(外人)」と書かれた看板がいたるところに立っている区画があり、そこに日本で亡くなられた外国人の方々のお墓があります。お墓は、十字架が立っているものであったり、読むことが困難な文字が刻まれていたり様々です。現在では行われないのですが、かつてはここも土葬でした。

S:ありがとうございます。それでは、日本社会というか日本人の埋葬や土葬などに関する意識はどうなのでしょうか。

石毛さん:宗教学者の山折哲雄さんは、「現在日本では、亡くなった人を葬儀せず、自宅や病院などから遺体を直接火葬場に送って火葬するケースが流行のように増えてきています、これは霊魂や他界の観念は消失し遺体を生ゴミのように死体処理するかのようで、生き残った者の都合だけがあるように感じられる」と主張されています。そしてまた「土葬は自然との循環の中にある人間という認識をもたらし、死生観に変化をもたらす良い機会になるのではないか」というように、土葬を肯定的にとらえています。このような意見を述べている方もいらっしゃるわけです。

他方で、日本に住んでいるイスラム教徒の方々に対して、「外国人が日本に住んでいるのだから、郷に入れば郷に従え、つまり火葬にしろ」と言う人もいるかもしれません。

しかし、逆の立場に立って考えてみましょう。

たとえば日本人が、インドに住んでいて亡くなった場合に、「あなたはインドに住んでいるので、インドのやり方に従ってください。火葬してガンジス川に遺体を流すか、あるいはチベットで亡くなり鳥葬つまり遺体を崖から投げてその遺体を鳥がついばむという葬儀のどちらかを選んでください」と言われたら、どう思われるでしょうか。なかなか受け入れ難い選択なのではないでしょうか。

一方で、日本では、こうした外国人のために土葬墓地をつくろうと計画が持ち上がっても、言語・文化の理解不足、宗教・埋葬方法の違い、偏見となど様々な要因から、「気味が悪い」「不衛生だ」などの意見や理由が壁となって拒まれているのが現状なのです。

S:そうですね。私もこのような問題や課題が起きていて、なかなか問題解決がなされていないと聞いています。他方、現在そして今後、外国人の方々の数が急速に増えることも予想されるなか、待ったなしの問題になってきているのではないかとも考えています。

ところで、日本における埋葬の実態はどのようになっているのでしょうか。

日本の埋葬の現実について

石毛さん:厚生労働省によると、日本における火葬場は、2000年度末には全国で7338カ所ありましたが、市町村合併などで4割減少し現在では4307カ所になっています。逆に死亡数は、2021年(人口動態統計の速報値)で、また死者数は感染力が強い新型コロナウィルスのオミクロン株の流行などにより、前年比67745人増の145万2289人となっています。そのほとんどが火葬であり、その数は戦後最多となっています。

さて、土葬と火葬という視点で考えた場合、世界の宗教人口(2020年約78億人)では、キリスト教31.3%イスラム教25.0%仏教6.3%などです。そのうち基本的に土葬するキリスト教とイスラム教の二つの宗教を合計しただけでも、土葬は56.30%と考えられ、過半数を占めているということができるのです。また中国や韓国では基本的には土葬です。

私たち日本人は、火葬があたりまえに思っているのですが、実は世界ではそれは必ずしもあたりまえではないのです。

しかし、その中国や韓国そしてヨーロッパでも、近年新型コロナウィルスなどでもみられるように衛生面や土地不足といった課題から、火葬を取り入れる国も増えてきています。火葬率でみると、日本は99.98%、台湾は96.19%、香港は93.34%です。

このように考えていくと、日本は、世界一の「火葬大国」であり同時に火葬を取り巻く技術や文化は世界のなかで最も進んだ国であるということができるのです。

S:そうなんですね。私は、そのようなことについて、あまり知りませんでした。では、そもそも「火葬」そのものについても、お話ししていただけませんか。

石毛さん:火葬の始まりを調べると、古くは遺体を古墳に納める、かまど塚と呼ばれる火葬様式のようなものが存在していたようです。また仏教の開祖、お釈迦様が荼毘(火葬)に付されたことや、戦後の高度経済成長期における都市化で深刻なスペース不足に陥ったことなどにより火葬が定着していったのです。

その火葬も、日本の長い文化や風習の歴史において、古代から江戸時代までは遺体を傷つける行為は罪とされる思想が強かったために土葬が主流だったのです。そして、火葬が土葬を数の上で上回ったのは、1935年頃からです、1970年代でもまだ8割程度にとどまっていたようです。なお現在のように、火葬場で重油やガスを燃料にする方式はここ100年ぐらいに過ぎないということができるでしょう。

S:はじめて知りました。ありがとうございます。

(注)日本では、墓埋法では土葬などの火葬以外の方法を禁じてはいません。しかし、行政は、環境衛生面から火葬を奨励しています。特に東京都(除島嶼部・八王子市・町田市、国立市等の10市2町1村)や大阪府などでは、条例で土葬を禁止しています。このことも、日本で土葬墓地を見つけることを困難にしているのです。

インタビュー対象者略歴:石毛泰道さん 徳雲寺住職

曹洞宗大本山総持寺独住第十八世の孤峰智サン禅師の門下である三輪悦禅大和尚の高弟三輪智明大和尚に師事し、石川県で約六百年の歴史を持つ同派北斗山徳雲寺住職になる。慶応大学文学部を卒業したのち早稲田大学大学院公共経営研究科博士k課程を修了。フランスの国立ストラスブール大学でも海外の文化や宗教を学ぶ。またアフリカ諸国に井戸や学校などを建設し、子ともたちの教育に貢献している。

徳雲寺の連絡先:tokuunjikongou@gmail.com

……次回に続く……

A cemetery for non-native. Is it available in Japan regardless of nationality and religion?

The number of resident aliens in Japan was 2,885,904 as of the end of June 2020, according to the Immigration Services Agency. From 2013 on the number of registered foreign nationals had kept on increasing and shown a new record high every year, until the trend began to decrease around February 2020 with the rapid spread of the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, as symbolized by the amended Immigration Control Act which entered into force in April 2019, labor shortages are becoming increasingly serious due to the dwindling birthrate and aging population in Japan. As this is the case, it is widely anticipated that the inflow of foreign workers will increase when the pandemic is over.

The share of foreign workers accounts for around 2% of the Japanese total population of 125.9 million, at a rough estimate. I think readers have realized this fact. For instance, you often see many foreign people working at nearby convenience stores, restaurants, construction sites and so forth. In this way, internationalization is going on in cities as well as in rural areas, so that foreign labor power is indispensable to maintain the Japanese economy. These foreigners have adapted successfully to Japanese society, while living normally with their families. In the process of this adaptation of non-native people here, there are some inevitable issues.

One of the most significant problems is the present situation of cemeteries for foreigners. More specifically, there are cases in which foreigners' remains are not accepted by Japanese cemeteries because of the difference in burial methods depending on nationality and tradition.

This article considers the above issue through an interview in two parts with Taido Ishige, who is the Chief Priest of Tokuunji Temple in Ishikawa Prefecture. Ishige has been making efforts to solve the issue as a religious specialist.

Suzuki (“S” below): I look forward to talking with you today. I know there are many problems with burials and cemeteries for foreign people who have passed away while resident in Japan. Considering the status and the future of Japan, these problems will become more and more important for non-native residents. To begin with, would you summarize the historical background and the current situation of the issue? I see the media have reported on problems associated with burials for Muslims in particular.

"Burials considered from the controversial issue of interments of Muslims"

Taido Ishige (“Ishige” below): According to a survey, the current population of Muslims in Japan is close to 200 thousand. It is anticipated that the number of immigrants from Islamic countries, such as those in Southeast Asia, will increase to meet the growing need for labor in the aging society with fewer children here. They say the population of Muslims here will exceed 300 thousand in 2050. As Islamic doctrine prohibits the intentional disfiguration of one’s body, the remains must be buried in the same condition as when the deceased was alive. Accordingly, the remains should be interred. However, there are only a few cemeteries where interments are allowed, due to restrictions in Japan (Note). In Kyushu area in particular, there is no such cemetery at all. As a result, in some cases it may not be possible to bury remains because of the overall insufficiency of cemeteries for Muslims where interments are allowed without requiring cremation. Therefore, the lack of cemeteries is a serious problem for Muslims in Japan.

S: I understand. Would you give examples of cemeteries where interments are allowed?

Ishige: For instance, Tama Reien (Tama Cemetery) in Fuchu City is one. There rest 426,786 mortals (as of April 1, 2021) in 128 hectares (27 times larger than Tokyo Dome, a popular baseball stadium in downtown Tokyo). This cemetery is celebrating the 100th anniversary of its opening in 1923. Recently, there is a growing tendency to dismantle family tombs and move to group graves or foreign cemeteries due to the absence of relatives to take care of the place or in order to avoid burdens on future generations. In a corner of this cemetery, there is a place where you find signboards reading “Foreigners” everywhere, indicating that there rest non-native people who have passed away in Japan. The tombstones are in various forms. Some of them have crosses, while others are engraved with foreign letters. This place used to be for interments, although it is not the case nowadays.

S: Thank you for the information. What is the general consciousness on burials among Japanese people?

Ishige: Tetsuo Yamaori, a religious philosopher, says, “It has become prevalent to send remains directly to crematories from homes or hospitals without funeral rites. The idea of the soul and the next world after death has been lost, so that remains are to be disposed of just like raw garbage. Only the convenience of survivors matters, I feel.” There are also affirmative opinions on interments that promote the idea of human beings within nature and the cycle of life, offering good opportunities to change views of life and death in Japanese society. On the other hand, other people might say, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” meaning that the non-native people should accept cremation since they live in Japan. Let us play the devil’s advocate here. For instance, imagine that you had lived and died in India. What would you say if you were told that your ashes should be thrown into the Ganges River in the Indian custom? Or would you be able to accept the so-called sky burial in Tibet, casting your remains over a cliff to feed the birds? I think it would be a difficult decision for you. In the meantime, it is very hard in Japan to develop cemeteries where interments are allowed for foreign people. These projects are likely to be refused in the face of opposing opinions such as “Interments are freaky” or “There are sanitation issues.” There is a lack of understanding regarding differences of language, culture, religion, and ways of burial, as well as prejudice against foreigners. I am afraid this regrettable situation stands regarding the issue.

S: I know the existence of the issue and that it has not been possible to resolve so far.

There is no time to waste for solving the problem, as the number of non-native people is expected to increase rapidly from now on. By the way, what is the current situation of burials in Japan?

Present situation of burials in Japan

Ishige: According to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, there were 7,338 crematories nationwide at the end of 2000. In 2021, according to the government’s rough estimate from the population statistics of the year, the number has fallen to 4,307, 40% down, due to the merging of municipalities and other reasons. On the other hand, the death toll increased to 1,452,289, up 67,745 compared to the previous year, caused by the prevalence of the highly contagious coronavirus Omicron variant and other reasons. In most cases, remains were cremated, so the number of cremations was the highest since World War Ⅱ. Out of the world total population of approximately 7.8 billion as of 2020, Muslims and Buddhists comprise 25.0% and 6.3% respectively, while Christians account for 31.3%. As Christians and Muslims are generally supposed to be buried, it is considered that interments form a majority of 56.3%. While Japanese people consider cremation a matter of course, it is not necessarily common from the global point of view. However, the number of countries where cremation is being introduced is continuing to rise, in expectation of resolving hygiene problems associated with the Covid-19 pandemic and the lack of land for burials. At present, the rate of cremation is 99.98 in Japan, 96.19% in Taiwan and 93.34% in Hong Kong. Accordingly, Japan ranks at the top in the world in terms of the number of cremations, with the most advanced culture and technologies regarding that funerary method.

S: I didn't know that. Would you tell us more about cremation, please?

Ishige: Looking into the origin of cremations, there was a kind of cremation called Kamado-zuka (stove-cemetery) in ancient times. They laid ashes to rest in tombs. I think the tradition of cremation gradually became rooted among Japanese people, supported by the historical fact that the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, was cremated. The serious insufficiency of land due to the rapid urbanization during the high economic growth period was also an important factor in making cremation the major funerary method in contemporary Japan. In the long history of Japan in terms of culture and customs, interments were predominant instead of cremation, as from ancient times through the Edo era (1603-1868), people strongly believed that damaging remains was not ethically permitted. It was around 1935 when cremations exceeded interments in terms of numbers. The ratio of cremations remained at about 80% in the 70s. It is only over the past 100 years that heavy oil and gas have been used as fuels at crematories as they are now.

S: That's news to me. Thank you very much.

Note: The Act on Cemeteries and Interment, Etc. of Japan does not prohibit funerary methods other than cremations, such as interments. However, administrative authorities recommend cremation, from the standpoints of the environment and the health of the nation.

Especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area (excluding outer islands, ten cities among which are Hachioji, Machida, and Kunitachi, two towns and one village) and the Osaka metropolitan area, interments are prohibited by local ordinances. This is one reason why it is difficult to find cemeteries for interments in Japan.

Brief biography of the interviewee: Taido Ishige, Chief Priest of Tokuunji Temple

Studied under the high priest Chimyo Miwa, a leading student of the high priest Etsuzen Miwa, who in turn was a follower of the Zen master Chisan Koho, 18th head abbot of the Soto Zen Buddhist Sojiji Temple.

Mr. Ishige is the Chief Priest of Tokuunji Temple, which belongs to the same sect as Sojiji Temple and has a history of about 600 years in Ishikawa Prefecture.

Education: Bachelor of Arts from Keio University. Doctorate from Graduate

School of Public Management, Waseda University.

Studied international culture and religion at Strasbourg University (France).

Foreign aid activities: He has contributed to African countries in child

education and construction of schools and wells, etc.

Contact e-mail address at Tokuunji Temple: tokuunjikongou@gmail.com

To be continued in the next interview.